Minimizing Injury in High-Risk Falls During Exoskeleton Use

Older adults fall frequently, and head trauma during a fall can be life-changing. This project explores how Hamilton–Jacobi reachability and reinforcement learning can work together to reduce head-impact severity when a fall with a lower-limb exoskeleton is unavoidable rather than preventable.

Course: Embodied AI Safety · Carnegie Mellon University

Advisors: Kensuke Nakamura & Prof. Andrea Bajcsy

I. Introduction – Why Safe Falling Matters

Exoskeletons are typically designed to make walking easier, but older adults consistently rank fall prevention and fall safety as the most important feature they want from these devices. Falls are common in this population, and head impact during a fall can cause severe neurotrauma, loss of independence, or even death.

Most current exoskeleton controllers focus on energy savings and gait assistance, not on what the device should do once a destabilizing push makes a fall inevitable. This project proposes a safety-critical control framework that explicitly targets the high-risk phase of a fall and aims to reduce the chance and severity of head impact.

Concretely, the objective was to integrate Hamilton–Jacobi (HJ) reachability analysis with Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) reinforcement learning in a physics-accurate MuJoCo humanoid model, and to evaluate whether this hybrid controller could learn safe falling strategies for a lower-limb exoskeleton user.

II. Methods – From Safety Specification to Simulation

A. Modeling the Fall and the Injury Risk

The starting point was a simplified lower-limb exoskeleton model that can apply torque at the hip and knee joints while the human body is represented by a 3D MuJoCo humanoid. The system state includes joint angles and velocities, as well as the three-dimensional position and velocity of key body segments, with a special focus on the head.

To capture injury risk, the project defined a failure set of states in which the head is on or through the ground, and an unsafe set of states from which head impact becomes unavoidable under worst-case disturbances. A signed-distance function combines head height and vertical head velocity to estimate how much stopping distance remains before the head would impact the ground at a tolerable deceleration level.

B. Hamilton–Jacobi Reachability for Safe Control

Hamilton–Jacobi reachability was used to approximate the backward-reachable tube of the unsafe set. A neural network learned a value function that maps each state to a safety value: positive values are safe, and negative values indicate states from which head impact cannot be avoided under worst-case disturbances.

The gradient of this value function provides a direction in state space that most quickly increases safety. When the safety value becomes negative or close to zero, the controller can override the nominal action and apply a “safety control” that steers the system away from high-risk configurations.

C. Safe Reinforcement Learning in MuJoCo

The safety analysis was embedded into a Soft Actor-Critic reinforcement learning loop. During simulation, the humanoid starts in a standing posture, then experiences a randomized horizontal push of 150–600 N to the torso after 0.5 s. From this moment on, the policy must decide how to use only hip and knee torques to manage the fall.

At each time step, the environment computes the safety value and its gradient. If the state is considered safe, the SAC policy chooses the action. If the state enters the backward-reachable tube, the safety control replaces the SAC action. The reward function penalizes low head height and adds an extra penalty when the safety value is negative, so the critic learns to assign low value to trajectories that pass through unsafe regions.

III. Results – What Worked and What Did Not

Training was run for 100 episodes, where each episode contained multiple epochs of simulated falls with varying push directions and magnitudes. Throughout these runs, the cumulative reward stayed negative, which suggests that the controller was unable to consistently prevent head contact with the ground.

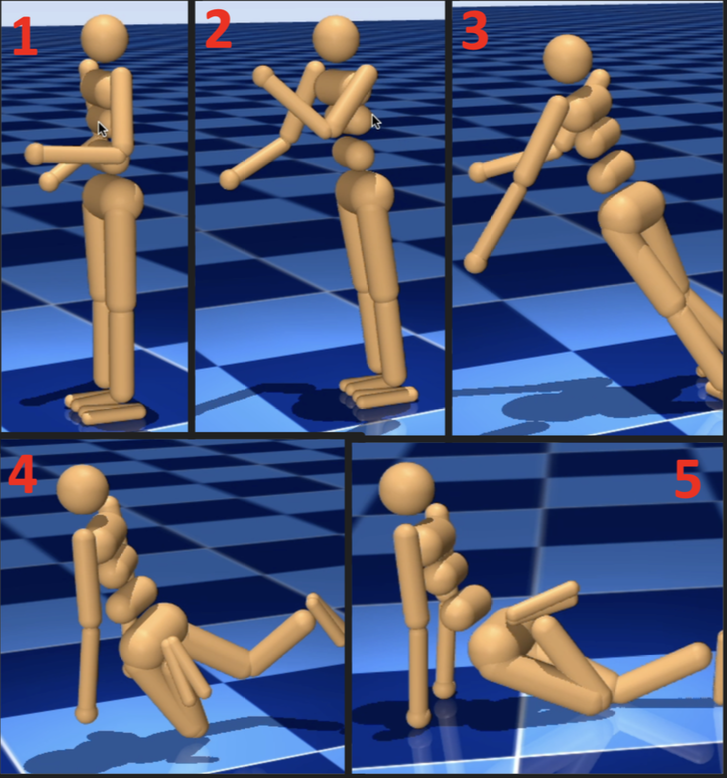

Visual inspection of the learned policies confirmed that the exoskeleton torques rarely generated large, coordinated motions that could meaningfully reorient the body. Even when actuator limits were relaxed, the controller did not discover strategies such as rotating the torso, tucking the head, or directing impact toward a safer body segment.

These findings show that, in its current form, the hybrid HJ–SAC framework did not yet produce a reliable safe-falling controller, but it did reveal several important design constraints and failure modes.

Evaluation – Interpreting the Negative Results

- Limited actuation: Restricting control to hip and knee joints may not provide enough authority to meaningfully change fall trajectories, especially when the upper body is modeled as passive and multi-segment.

- Reward shaping: The safety penalty is large at the beginning of training, which prevents the SAC policy from discovering even moderately helpful behaviors before the value function becomes reliable.

- High dimensionality: Learning an accurate safety value function for a full humanoid is challenging, and implementation bugs or approximation errors can easily obscure the intended backward-reachable tube.

- Modeling choices: Making the upper body completely rigid prevents realistic failure modes, while leaving it fully articulated makes the control problem harder. Both extremes affected how informative the training data was.

IV. Discussion – Toward Safer Exoskeleton Falls

Even though the controller did not converge to a successful policy, the project demonstrates how safety analysis can be tightly integrated with modern deep reinforcement learning. The work also clarifies when that integration may fail, for example when the safety penalty overwhelms the task reward or when the control authority is fundamentally insufficient.

A promising next step is to reformulate the problem as safe trajectory tracking rather than as a static “avoid head impact” condition. In that view, Hamilton–Jacobi reachability could guarantee that the exoskeleton can still follow a pre-designed safe-fall motion under worst-case pushes, making martial-arts-inspired strategies like UKEMI more realistic for exoskeleton users.

Future simulations on lower-dimensional models such as Walker2D, followed by richer sensing and possibly additional hardware (for example, deployable supports), could bring this framework closer to a deployable safe-falling system for real users.

V. My Role and Contributions

I led this project from initial concept to final report, with responsibility for both the control-theoretic design and the simulation infrastructure.

- Problem and safety specification: Defined the exoskeleton fall-safety problem, formulated the failure and unsafe sets, and designed the signed-distance function that encodes safe stopping distance for the head.

- Control and learning framework: Implemented the Hamilton–Jacobi value function approximation, integrated it with Soft Actor-Critic, and designed the safety-aware reward structure.

- Simulation pipeline: Built and modified the MuJoCo humanoid environment, scripted the randomized push experiments, and managed data logging and visualization for training runs.

- Analysis and reporting: Diagnosed failure modes, proposed redesigns for future work, and wrote the full technical report and presentation materials summarizing lessons learned for exoskeleton safety research.

Together, these contributions highlight my focus on safety-critical robotics, safe reinforcement learning, and the practical challenges of translating theoretical guarantees into embodied systems that protect real people during falls.