Introduction

Many stroke survivors, veterans with neurotrauma, and older adults rely on assistive devices but still face a high risk of falls while walking or standing in dynamic environments such as buses and trains. Exoskeletons can apply corrective torques at the hip, knee, and ankle faster than humans can react, yet current controllers struggle with two challenges: maintaining balance under unpredictable platform motion, and collecting enough person-specific gait data to personalize assistance.

This project investigates two complementary solutions. First, I design a linear–quadratic regulator (LQR) that keeps a simulated humanoid balanced on a randomly moving platform, with and without added support structures like railings and a hip exoskeleton. Second, I use iterative linear–quadratic Gaussian control (iLQG) to transfer a real person’s gait from motion capture data into simulation, enabling the future placement of virtual IMUs and rapid, personalized controller tuning without extensive lab data collection.

Methods

LQR balancing on a moving platform

I built on DeepMind’s MuJoCo humanoid model with 27 degrees of freedom and 21 torque-controlled joints. After linearizing the dynamics around an upright standing pose, I solved the discrete-time algebraic Riccati equation to obtain an LQR state-feedback controller that regulates the humanoid’s state while the floor undergoes random velocity perturbations in the forward– backward direction.

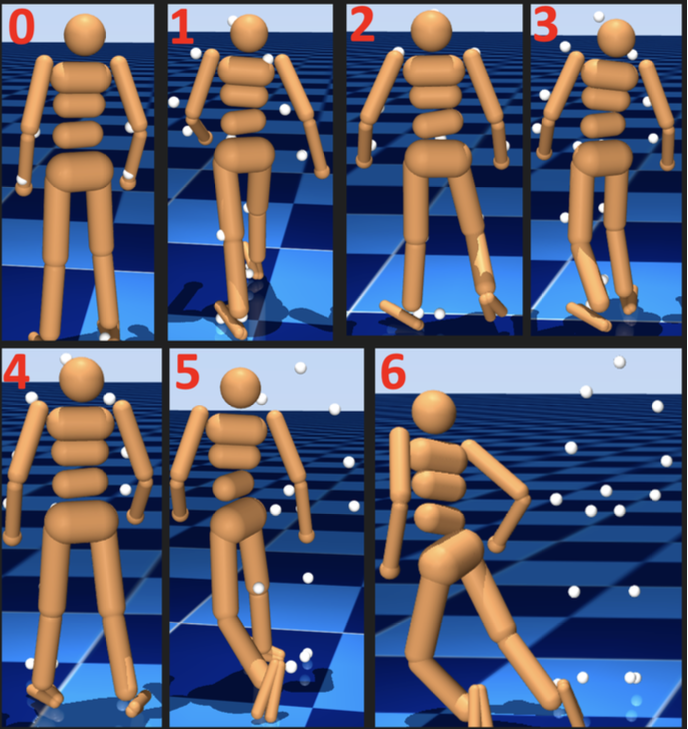

To understand how physical aids affect stability, I ran four experiments:

- Experiment 1 – Fixed feet: both feet were welded to the platform to test the best-case stabilization performance.

- Experiment 2 – Free feet: the constraints were removed so the controller had to manage ankle and whole-body dynamics without enforced contact.

- Experiment 3 – Railing support: I added a waist-height railing and extended the cost function to keep the hands near the rail, encouraging the humanoid to use it for support.

- Experiment 4 – Hip exoskeleton: I modeled a simplified hip exoskeleton as hinged rods along each thigh, disabled the humanoid’s native hip motors, and applied LQR control through the exoskeleton actuators.

iLQG real-to-sim gait tracking

To generate personalized synthetic gait data, I used iLQG to track human motion in MuJoCo. I warm-started the optimization with a model predictive control (MPC) walking policy and aligned it in time with a real walking trial from the CMU motion capture database. For each frame, I defined a cost that penalized deviation between 16 selected humanoid keypoints and (1) the mocap keypoints and (2) the MPC reference gait, along with a control-effort term.

MuJoCo’s analytical Jacobians provided the linearized dynamics and cost derivatives for the backward Riccati pass. After computing feedback gains, I performed a line search over control updates, accepted trajectories that reduced total cost, and rolled them out to iteratively refine the walking policy.

Results

LQR balance robustness

With fixed feet (Experiment 1), the LQR controller maintained balance even when the platform experienced random velocities between –5.1 m/s and 5.1 m/s at every time step. When I removed the foot constraints (Experiment 2), the maximum tolerable perturbation dropped sharply to about 0.36 m/s, showing how strongly platform–foot coupling contributes to stability.

Adding a railing (Experiment 3) modestly improved robustness, increasing the maximum stable perturbation speed to roughly 0.45 m/s as the humanoid learned to lean on the rail. The hip exoskeleton in Experiment 4 successfully balanced the humanoid under smaller perturbations (about ±0.1 m/s) and produced hip-joint angle trajectories that closely matched the exoskeleton’s commanded torques, confirming correct coupling between exoskeleton actuation and leg motion.

iLQG gait-tracking performance

After tuning the relative weights on mocap tracking, MPC consistency, and control effort, the iLQG controller reproduced the subject’s walking pattern for an average of 4.8 seconds (± 1.06 s) out of a 7-second trial across 30 runs—roughly 70% of the full trajectory. Beyond this horizon, accumulated errors triggered large corrective torques that destabilized the humanoid and led to a fall, highlighting where better dynamics alignment and torque constraints are needed.

Discussion & Impact

Together, these studies show that optimal control can both stabilize exoskeleton users and reduce the data burden of personalization. The LQR experiments provide a clear picture of how design choices—such as railings or hip exoskeletons—change the range of disturbances a person can safely tolerate. The iLQG pipeline demonstrates that we can start from a few seconds of motion capture data and create a physics-consistent walking model that is suitable for placing virtual IMUs and exploring sensor layouts before running physical experiments.

In future work, I plan to expand the exoskeleton model to multiple joints, add realistic mass and contact forces, track joint angles directly rather than sparse keypoints, and use the synthetic data to train learning-based exoskeleton controllers (such as temporal convolutional networks) that include LQR-style safety overrides for extreme disturbances.

My Role

- Defined the research problem around fall prevention and exoskeleton personalization and led the overall project.

- Implemented the MuJoCo humanoid simulation environment, moving platform, railing, and simplified hip exoskeleton models.

- Derived and coded the LQR controller, designed all four balance experiments, and analyzed perturbation-robustness results.

- Built the iLQG tracking pipeline, including cost design, warm-start with MPC trajectories, and integration of CMU mocap data.

- Performed result analysis, created figures and videos, and wrote the project report summarizing implications for future exoskeleton controllers.